How Botswana Built a Successful Anti‑Corruption Agency: Directorate on Corruption and Economic Crime (DCEC) Case Study & Lessons Learned

- Alvin Kumar

- Feb 13, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Jul 10, 2025

This post is adapted from a couple of academic papers written in 2021.

Corruption is the abuse of power for illicit gain. To fight corruption in a meaningful manner we need action to be taken at all levels, from online, local grassroots and regional groups to government agencies and supranational institutions. In this post we'll dig into the Anti-Corruption Agency (ACA) as a tool for fighting the good fight, focusing on a particular agency, its inception and activity.

Introduction - Botswana

We are looking at a onetime anti-corruption superstar that has lost its lustre a touch but remains an exception to many rules, pun intended.

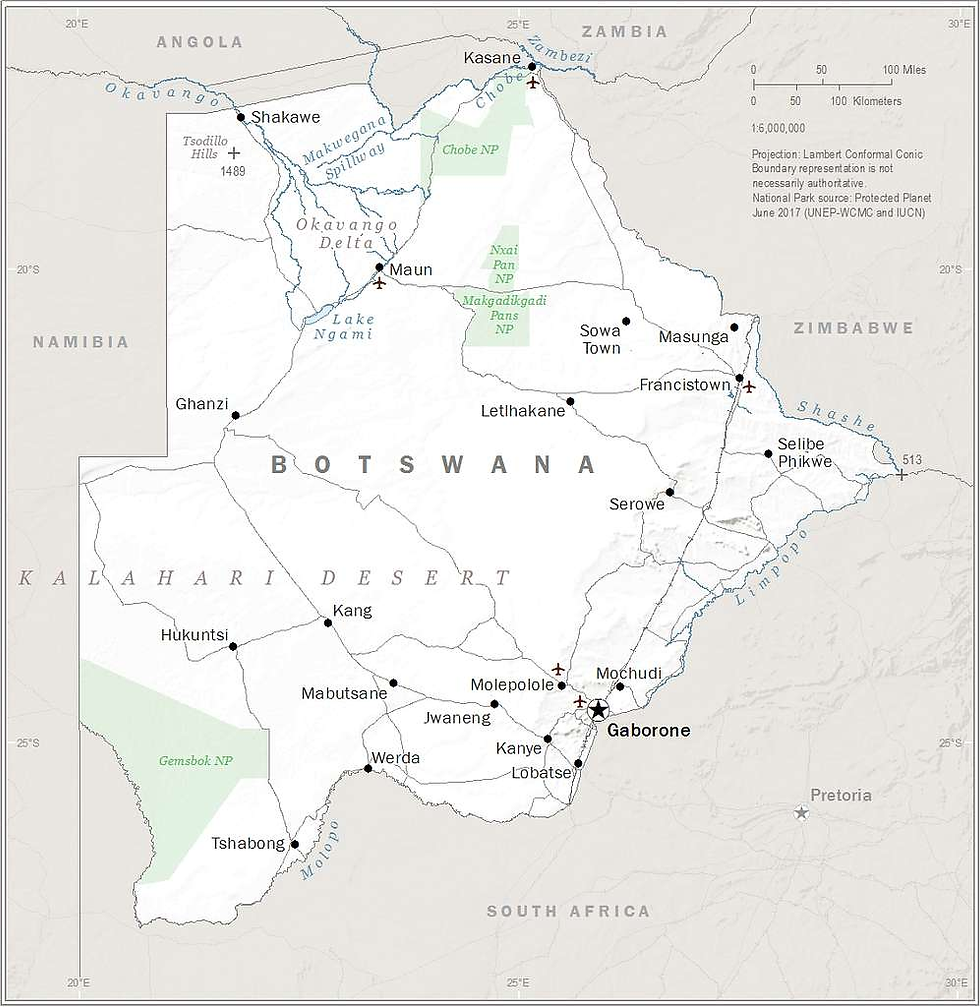

Post a period of democratisation following independence from the British in 1966, Botswana came to be seen as having a solid Constitution and a strict approach to corruption. Benefitting from not having had a military government, or suffered authoritarian rule - though it was annexed by the British for a period - it maintained a stable, developing democratic government (Sebudubudu, D. 2003, p. 125), but not without its issues. The population is around 2.5million, with the capital Gaborone housing approximately a tenth of that number. The geography of the country is dominated by the Kalahari dessert which covers roughly 70% of the land mass, this has separated rural populations to a degree, making communication at grassroots a challenge.

The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) has ruled continuously since 1966, elections are deemed to have been largely fair, a stability rarely seen in Africa. It is counter to the idea/example that long-standing ruling parties can only maintain their positions via tyranny, such as (competitive) authoritarian regimes where rulers or ruling families lead for many years enabled by injustice and corrupt activities; see Nguema in Equatorial Guinea, Nguesso in Congo Brazzaville and Putin in Russia (not Africa obviously but an unfortunately excellent example - further posts to follow on Russia and their poster boy for corruption).

However, in the early 1990s there were a number of high-profile corruption scandals relating to business tenders for government infrastructure projects. At this time the police were accountable for fighting corruption and fraud. In 1994 the Botswanan Directorate on Corruption and Economic Crime (DCEC) was established as a permanent agency, under the Corruption and Economic Act 1994, as these scandals threatened Botswana’s developing democracy and hopes of good governance. Government, press and public were aligned at DCECs inception and this citizen driven aspect was key creating and maintaining a meaningful dialogue.

The approach of Anti-Corruption Agencies (ACA) varies dependent on their motivations, resources and powers held. Success for these entities is a matter of context and perspective, both local and global, subjective and objective.

When setting up an ACA, in this case the DCEC (acronyms aplenty), the fundamental question and primary concern has to be, what works when fighting corruption? You have to start with a strong institutional framework, so we'll look at the idea of successful vision and inception of an ACA. Next we'll consider success and prevention in the context of education and collaboration, and suggest an addition to the threefold approach of investigation, education and sanctioning which underpin the role of an effective ACA. Collective action is vital in many a movement, the active collaboration and integration across areas such as enforcement agencies, civil society, education, international treaties, bottom-up movements, and top-down approaches will be explored.

The DCEC – an ACA built with intent.

The early 1990s in Botswana saw high-profile corruption scandals threaten the good standing and economic development of the country - construction, education supply chain and infrastructure projects amongst others were compromised. The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) having ruled since 1966 found itself facing public scrutiny and discontent (Kuris, G. 2013, p. 1-3; Transparency International. 2014 p. 1).

Under the Corruption and Economic Crime Act 1994 the DCEC was created (also 1994) to focus on education, prevention and investigation in the myriad realms of corruption, the agency was organised into various divisions including investigations, legal service, anti-money laundering, public education and corruption prevention. The inception of the DCEC was overseen by former police investigator and then deputy commissioner of the lauded Hong Kong Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC), Graham Stockwell, who become the first lead/director of the DCEC. Stockwell was engaged and passionate, his initial approach was geared towards sustainable and tactical development, raising awareness and creating public discourse on the subject. The planning and strategic development outlined by Kuris (2013) was evidently comprehensive, a moral, optimistic and ardent approach, hence a deliberate and well considered foundation was laid (Kuris, G. 2013, p. 1-6).

As De Sousa (2010) states that “technical, statutory or cultural” difficulties can arise during this process and that ACAs created amidst scandals can deteriorate and be limited by their initial focus. The DCEC architects seem to have mitigated this by persuading an experienced, astute and invested Stockwell to take the lead and not just consult. De Sousa (2010, p.12 – quoted) again points out the potential pitfalls in his conclusion and the DCEC fairs well;

“…little care in choosing their format, location and in setting adequate management strategies from the outset; even lesser care with regard to their financial autonomy; expectations inconsistent with the available resources (financial, human, knowledge); unfit recruitment and reporting/accountability arrangements.”

The DCEC has a inherent potential concern in its connection to Office of the President, this is seen as a point of reduced autonomy. Some might say that convincing one man to take action would be preferable to convincing parliament. These points were largely met head on by Stockwell, who within his remit was careful to not allow a such hinderances (Kuris, G. 2013, p. 1-6).

The approaches taken were successful due to a strategic approach and diligence at each stage of development, the experience and staff Stockwell brought with him were crucial to the success of the newly minted DCEC. Initially the powers granted in the Corruption and Economic Crime Act were substantial, though the political ownership and will, support for Stockwell, alongside support from and engagement with civil society and the public was key. The DCEC recognised its challenges and though influenced by the HK ICAC it did not take a prescriptive one-size-fits-all approach.

Stockwell initially brought in external contractors to set up the DCEC and bolster the ranks while setting up and training local investigators, this set-up was an international collaboration. When the Botswanan delegates went to London to seek assistance in the initiation of the DCEC they entered the international anticorruption arena and were pointed in the direction of Stockwell at the HK ICAC. There was intent in the creation of the DCEC, and it was a momentous example of international multi-lateral cooperation and collaboration.

According to Meagher (2005), there are several factors that can increase the chances of success of an ACA; sufficient resources, power to sanction, independence, cooperation from sister agencies, public accountability and support. As per the power Stockwell had, he saw to it that the DCEC had a successful start.

Life in the danger zone

Africa is a continent besieged with corruption and Botswana is often held up as the beacon of hope in a quagmire of anticorruption stagnation (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2018). In reality of course Botswana and its DCEC face a multitude of challenges and very real instances of embedded corruption. Molebatsi and Dipholo (2014) note that “patronage, nepotism and cronyism are prevalent in the Botswana public service” with family and close contacts benefitting from connections to win tenders (Mudeme, K & Holtzhausen, N. 2018), an unfortunate phenomena commonly referred to as ‘tenderpreneurship’ in academia and political commentary.

The idea of cliques of politicians, business folk, bureaucrats, military and social leaders creating networks and structures that benefit themselves is nothing new. Micheal Johnston (2012, p 469) has applauded Botswanas approach but he has also placed it firmly in the category of Elite Cartels, one of four Syndromes of Corruption (+ Influence Markets, Oligarchs and Clans, and Official Moguls) he has pegged, and states (2005, p118) “…it was not corruption as such that produced growth, but rather an elite whose policies were solidified and made credible in corrupt ways.” In addition to providing their chosen few with corrupt advantages, elite cartels are able to form alliances and networks that strengthen their hold on power and ward off opposition. Although this kind of corruption can be very profitable, it is also a tactic used to thwart political reform. This particularism keeps the competition at bay whilst strengthening governance by reduced fractionalisation, and maintaining - on the surface - a mostly fair and just democracy alongside sustained economic growth - this is a complex polymorphous reality.

As the DCEC is held back by political and anticorruption platitudes, Botswana has seen itself slide 5 points in the Corruption Perception Index since 2012, and Afrobarometer results (Sebudubudu, D. 2014, p7). Showing it is prone to the realities of its neighbours, but not so much so that it will capitulate.

This susceptibility can come from unfair elections, a lack of political will, poor governance, lack of resources, absence of public expectation and pressure, and the pitfalls in the existence of mineral wealth. While Botswana has the potentially unfortunate fortunes underground in the form of diamonds, it fortunately doesn’t suffer heavily from the formerly mentioned vulnerabilities. Despite the inherent flaws of the elite cartel that has been running the show since 1966, the DCEC does stay largely true to its original design and mission; investigation, education and prevention. According to Johnston (2012, p. 469) Botswana teaches other countries important lessons about the value of socially rooted leadership. Despite the obvious inconsistencies this rootedness is inherent in the political and social fabric of Botswana, a priori in their own particular ways neither the government, civil society or the public want corruption to prevail.

Education > Excuses

As education, healthcare and the economy often bear the brunt of corrupt ongoings, it is not entirely so in Botswana. The actions of the DCEC and political will to succeed in a particularistic fight against corruption have nevertheless brought forward a system that works and is not just for show. Literacy is high, health indicators improve solidly and the economic growth has been largely steady (CIA Factbook 2021).

Education is often a primary victim of a corrupt regime; it is also the key to creating an ongoing and intrinsic dialogue in countries that are susceptible to corruption. Education is responsible for its own survival, but it requires enablers and, in the DCEC, a vital contributor exists. DCECs approach to education and therein, public guidance and collaboration has been an important facet of their success and a successful image.

As per the UNODC Country Report for Botswana (2019), the DCEC are engaged in primary schools, presenting ideas of morality and corruption, secondary schools and colleges include anticorruption in the curriculum at some level, and all create Anti-Corruption Clubs. This approach on awareness and understanding at young age which is then built on throughout the education system is invaluable in the wider fight.

In a country where anti-corruption is already seen as a boon, instilling the sense of pride and understanding at the school level is an important way to create an ongoing dialogue and anticorruption heroes of the future. It is increasingly important that the government and the DCEC make the field an attractive one and relay its ongoing importance, especially since shortages in skilled staff at the DCEC have been noted (UNODC, 2019 p. 16). The draw of the private sector and brain drain are very real threats to the future of administrative justice.

Collaboration > Complacency

There are numerous potential avenues for collaboration for the DCEC, international agencies, government ministries home and abroad, the police, education, grassroots anticorruption agencies. These collaborative efforts, sharing resources, building networks, promoting awareness, etc. can be aligned with the goal of prevention and education, though as an area of focus collaboration deserves its own headline.

Civil society has leveraged the power and reach of the UNODC and UNCAC to empower themselves creating platforms for constructive collaboration and accountability. The UNCAC coalition is a network of over 350 civil society coalitions “committed to advancing the monitoring and implementation of the UNCAC, ” (Making UNCAC work, 2021. p1). This is an interesting amalgamation and integration of top-down and bottom-up approaches.

The DCEC actively engages with civil society under the UNCAC banner. Botswana Watch notes the DCEC consulted them through a questionnaire to provide input for the Second UNCAC Review Cycle The Botswana Centre for Public Integrity (BCPI) is another member of the UNCAC coalition, as is the Botswana Council of Non-Governmental Organisations (BOCONGO), who have a memorandum of understanding with the DCEC (UNCAC Coalition, 2021).

Locally the DCEC partners with the Office of the Ombudsmen, the Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Board (PPADB) and the Financial Intelligence Agency. In addition, Anti-Corruption Units (ACUs) have been set up at the ministry level to monitor transactions alongside corruption and report back to the DCEC. They also hold sector specific workshops on anti-corruption in sectors such as construction, IT and procurement (UNODC, 2019 p. 28, 17, 6). Whether the engagement with these sectors incorporates the Sector, Focus Reformulation Approach (SFRA) of Heywood and Pyman is unknown (Curbingcorruption.com/SFRA-2). And while certain relationships may be deemed as oversight roles, these cannot be successful without collaborative effort for a mutual goal.

On the international stage, as noted by Kuris (2013) DCEC staff have travelled to other ACAs to study and train, it has also developed a ‘college-level anti-corruption course in league with the University of Botswana’ with which it also holds a memorandum of understanding (UNODC, 2019. P. 6).

Engagement in rural areas (via radio, visits and presentations) might have been something that was overlooked or put on the shelf for logistical or budgetary reasons, but this has not been the case. A unique feature of Botswana is the low population density, amongst the lowest in Africa with approx. 4.1 people per square kilometer (UN World Population Prospects, 2019). This creates the opportunity for an excuse, an easy to ignore niche, but the opposite seems to have occurred the nature of the country’s geography was taken into account on inception of the DCEC and the rural population was immediately a consideration (Kuris, G. 2013, p.10-11).

As Hechler et al (2011) have noted, “UNCAC has been criticised for its weaknesses, especially with respect to political corruption, private sector corruption, and asset recovery.” Though it has its detractors, what it does well at the bottom-up level is provide a foundation for an interested party to join the fight and engage with agencies and organisations at any level. The frameworks within UNCAC have been successful in bringing grassroots organisations together, granting them legitimacy and a platform to make their presence felt, engage and contribute to action taken. Via broad and considered collaboration the strength of the DCEC education and prevention measures have been a success.

Conclusion

Success can be as simple as a single novel initiative achieved in challenging circumstances. What started as a success via intent and a measured strategy, has continued as one with collaboration at its core in the realms of education and prevention.

It is clear that the DCEC and the Botswanan fight against corruption faces many challenges, but the collaborations and education on the ground level are an increasingly important facet of their approach, inspiring the next generation to become part of the government ministries and agencies, entrepreneurs or socially engaged workers, should be done with the anticorruption message in mind. The UNODC Country Report states improved awareness and corruption reduction as observed successes, this is thanks to education and collaboration (UNODC, 2019. p.16).

On a macro scale in any moral movement, or pursuit of efficiency, the more interest, engagement and collaboration there is, the more likely the inception of novel, relevant and well considered outcomes might be reached. When politics and bureaucracy intervene the challenges for any policy can quickly become insurmountable. A priori, if managed correctly, the more people, and organisations involved, the more awareness, education and cross-pollination, the more likely we are to see success. Collaboration on various levels is of importance in the fight against corruption, it may have been overlooked as a pillar in the three-fold approach; however, it stands strong in the DCEC approach and the global fight against corruption.

While the DCEC isn't perfect, it has been an important instrument in the fight against corruption and keeping those in power in check, what's for sure is that without it Africa might be without an example of an anti-corruption success story.

Thanks for reading.

A. Rottenburger.

Bibliography

CIA World Factbook 2021, Available at: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/botswana (Accessed: 13 December 2021).

Corruption Economic Crime Act, 1994. Available at: https://publicofficialsfinancialdisclosure.worldbank.org/sites/fdl/files/assets/law-library-files/Botswana_Corruption%20and%20Economic%20Crime%20Act_1994_EN.pdf (Accessed 13 December 2021)

Corruption Perceptions Index (2020) Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020/index/nzl (Accessed: 14 December 2021).

DCEC Areas of Responsibility and key functions, (2021). Available at: https://cms1.gov.bw/ministries/directorate-corruption-and-economic-crime (Accessed: 13 December 2021)

De Sousa, L (2009). ‘Anti-Corruption Agencies: Between Empowerment and Irrelevance’ Available at:

https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/10688/EUI_RSCAS_2009_08.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed: 18 December 2021).

Financial Action Task Force/FATF (2010), A Reference Guide and Information Note on the use of the FATF Recommendations to support the fight against Corruption.' Available at: https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/reference%20guide%20and%20information%20note%20on%20fight%20against%20corruption.pdf (Accessed: 24 November 2021).

Hechler, H. Zinkernagel, G F. Koechlin, L. Morris, D. (2011). ‘Can UNCAC address grand corruption?’

Available at: https://www.u4.no/publications/can-uncac-address-grand-corruption (Accessed: 14 December 2021).

Heywood, PM (ed.) 2014, Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption, Taylor & Francis Group, London. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. (Accessed: 24 November 2021).

Johnston, M. (2005) Syndromes of Corruption. Cambridge University Press. pp.118

Johnston, M. (2012) Why do so many anti-corruption efforts fail? NYU Annual Survey of American Law. pp482. Available at: http://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/upload_documents/NYU-Annual-Survey-67-3-Johnston.pdf):467–496. (Accessed: 18 December 2021).

Kuris, G. (2013), Princeton University, ‘Managing Corruption Risks: Botswana Builds An Anti-Graft Agency 1994 – 2012.’ Available at: https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/sites/successfulsocieties/files/Policy_Note_ID233.pdf (Accessed 14 December 2021)

Matlhare, B. (2006) An Evaluation of the Role of the Directorate on Corruption and Economic Crime (DCEC) Botswana pp16-19. Available at: http://etd.uwc.ac.za/xmlui/handle/11394/1832 (Accessed: 20 November 2021).

Mauro, P. (1996). ‘The Effects of Corruption on Growth, Investment, and Government Expenditure’. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=882994 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.882994 (Accessed 13 December 2021).

Meagher, P. (2005) ‘Anti‐corruption agencies: Rhetoric Versus reality’, The Journal of Policy Reform, 8:1, 69-103, DOI: 10.1080/1384128042000328950

Molebatsi, R.M. and Dipholo, K.B. (2014). ‘Least corrupt Botswana: image betrayed.’ Journal of Public Administration. Pp. 49(3):794–802

Mphendu, U & Holtzhausen, N. (2016). ‘Successful Anti-corruption Initiatives in Botswana, Singapore and Georgia Lessons for South Africa.’ Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343263353_Successful_Anti-corruption_Initiatives_in_Botswana_Singapore_and_Georgia_Lessons_for_South_Africa/citation/download (Accessed: 21 November 2021).

Mudeme, K & Holtzhausen, Natasja. (2018). Contextualising Bureaucratic Corruption in the Botswana Public Service. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343263285_Contextualising_Bureaucratic_Corruption_in_the_Botswana_Public_Service (Accessed: 14 December 2021)

Sebudubudu, D. 2010. The impact of good governance on development and poverty in Africa: Botswana – a relatively successful African initiative. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations. 4(7):249–262, p251. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228629512_The_impact_of_good_governance_on_development_and_poverty_in_Africa_Botswana-a_relatively_successful_African_initiative (Accessed 21 November 2021).

Heywood, P. Pyman, M. Sector Focus Reformulation Approach model for tackling corruption, 2021. Available at:

https://curbingcorruption.com/sfra-2/ (Accessed: 19 December 2021).

Reporters without Borders, (2021). ‘World Press Freedom Index 2021.’ Available at: https://rsf.org/en/botswana (Accessed: on 18 December 2021)

Sebudubudu, D. (2014) 'Background paper on Botswana' pp. 4-5. Available at: https://anticorrp.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Botswana-Background-Report_final.pdf (Accessed: 19 November 2021).

Transparency International, (2014). ‘Overview Of Corruption and Anti-Corruption

In Botswana.’ Available at:

https://www.transparency.org/files/content/corruptionqas/Country_Profile_Botswana_2014.pdf (Accessed: 17 December 2021)

UNCAC Coalition (2021). Botswana Members. Available at: https://uncaccoalition.org/anti-corruption-platforms/africa/botswana/ (Accessed: 18 December 2021)

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (2018), ‘Botswana is a shining beacon of hope in the fight against corruption in Africa.’ Available at:

https://web.archive.org/web/20200930062530/https://www.uneca.org/stories/botswana-shining-beacon-hope-fight-against-corruption-africa (Accessed 13 December 2021).

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2019. Country Review Report of the Republic of Botswana (2019) Available at:

https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNCAC/CountryVisitFinalReports/2019_06_03_Botswana_Final_Country_Report.pdf (Accessed: 14 December 2021).

United Nations, (2019). World Population Prospects 2019. Available at:

https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ (Accessed: 18 December 2021).

The World Bank (2021). The World Bank in Botswana. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/botswana/overview#1 (Accessed: 19 December 2021)

Comments